Introduction

Managing human capital in an environment characterized by down-sizing, right-sizing, reengineering, technological innovation, and global competition is increasingly challenging for organizations. An effective strategy for managing the internal attributes of an organization must rely heavily on the capabilities of people to provide a competitive edge. Barney (1995) describes four internal attributes important to an organization’s ability to develop, manage and deliver products and services: physical, financial, organizational, and human. Of these, the human element is the cornerstone of the internal resources of an organization, and effective management of this element can make or break a business or other entity.

Enhancing the effectiveness of people in organizations requires consideration of a number of factors. The purpose of this article is to summarize relevant recent literature related to these dimensions, and present a conceptual model for effective management of the human element of the organization. The dimensions are summarized into five categories: fit, attitudes, compensation, empowerment, and selection (FACES). Components of the FACES model are:

1. Fit - matching an employee’s attributes to an appropriate employment climate, often

2. Attitudes - recognizing the importance of employee attitudes and satisfaction with the employment environment.

3 Compensation - considerations of effective compensation and performance management systems.

4. Empowerment - elements of employee success, development and wellness.

5. Selection - effective methods for selecting appropriate employees.

Fit

Matching people with appropriate organizations has a number of positive benefits. Perhaps the most important effects derived from matching individuals to the organization’s environment were determined through a study by Bretz and Judge (1994). Their study found that person-organization fit accounted for statistically significant increases in both tenure (up to 11 percent of the variance) and job satisfaction (up to 32 percent of the variance).

Rynes and Gerhart (1990) found that interviewers rate applicants differently on general versus firm-specific criteria. Interrater reliability was higher for firm-specific criteria than for general employability criteria, suggesting that interviewers in the same organization share common ideas about applicant-organization fit. This research was confirmed by Adkins, Russell and Werbel (1994), who also found that recruiters perceptions of person-organization fit are distinct from those of general employability. Adkins, et al. (1994) noted that higher person-organization fit ratings were associated with similarities in work values between recruiter and applicant.

Barrett (1995) examined person-environment congruence as measured by the Performance Priority Survey (PPS). This survey requires supervisors and subordinates to indicate priorities for behaviors important to the subordinate’s job. Correlations between scale values are assigned to assess the degree of congruence between supervisor and subordinate scores in two areas: applicant-supervisor pairs and applicant-organization congruence.

The author hypothesized that significant agreement between subordinate and supervisor would predict the supervisor’s satisfaction with the employee. Also, “high agreement between the applicant and organizational climate would lead to the prediction that the applicant would fit the organization” (p.658).

Barrett (1995) analyzed three studies which utilized the PPS to determine correlations of agreement scores and applicant-supervisor and applicant-organization fit. Analysis of the agreement ratings through various jobs and organizations revealed a moderate positive correlation between agreement scores and supervisor ratings of subordinates, and to a lesser degree subordinates’ rankings of supervisors.

Correlations between agreement scores of subordinates with averaged supervisor scores, postulated to be representative of organizational climate, indicated that agreement scores correlated with supervisor performance ratings. This correlation showed predictive validity for organizations with which the employee had no prior contact and for organizations with which the employee was familiar.

Employers should note that recruiters apparently distinguish between general employability of an applicant and an applicant’s suitability for a particular organizational environment. Given the associations between person-organization fit and tenure and satisfaction, employers should consider congruence between applicant and organization.

Attitudes

A recent survey by Hewitt Associates, LLC, found that, of 46,500 employees from 38 companies, 74 percent reported general satisfaction with their work, (“How satisfied”, 1997). The work itself and people/coworkers received the highest satisfaction ratings, with advancement opportunities, recognition and pay issues ranked the lowest.

Issues related to employee attitudes and satisfaction are important to the assessment of how human resources management and planning contribute to performance objectives (Morris, 1995). Morris (1995) recognizes seven elements related to employee satisfaction.

1. The job itself - including content, variety, training.

2. Supervisor relationships - related to respect, recognition, feedback and fairness in evaluation.

3. Management beliefs - related to trust, information sharing, and valuing employees.

4. Opportunity - for career advancement and job security.

5. Work environment - physical facilities, availability of resources.

6. Pay, benefits, rewards - compensation and rewards.

7. Co-worker relationships - cooperation, teamwork, communications.

These categories are evidenced in the Hewitt Associates survey results. Lieber (1998)summarizes the components needed for high levels of satisfaction into only three categories: inspiring leadership, great facilities, and a sense of purpose for employees.

Chase (1996) claims that even reengineering, done properly, can result in improvement in employee attitudes and satisfaction. Chase (1996) indicates that reengineering efforts related to processes benefit from employee input, and that input can be encouraged in a non-threatening (e.g. no job reductions) manner.

Further, involvement of people in studying processes can result in increased levels of trust.

Discussion of person-environment fit indicated possible connections between a match between employee and organization and job satisfaction. This relationship was explored by research conducted by Sims and Kroeck (1994)in terms of the ethical climate of a firm. They found that employees choose to work for companies that have ethical climates similar to that expressed by their preferences, that this similarity was negatively associated with turnover intentions, and that similarity increased organizational commitment. The relationship between ethical climate and job satisfaction was not statistically significant. However, both organizational commitment and negative turnover intentions imply some degree of satisfaction.

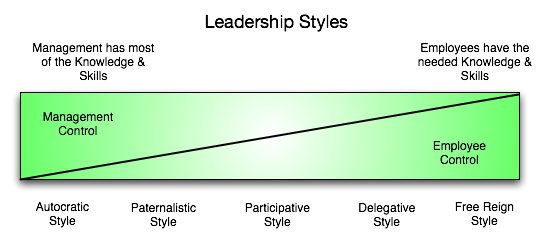

A study of the impact of leadership styles on employee attitudes was conducted by Savery (1993). This research investigated the connection between closeness of fit between perceived and desired leadership styles and job satisfaction. Additionally, it was hypothesized that perceived democratic leadership would have a positive impact on job satisfaction. This study confirmed that smaller differences (or dissonance) between perceived and desired leadership styles correlated with greater job satisfaction. However, perceptions of democratic leadership style did not necessarily lead to increased job satisfaction. In sum, the actual leadership style is less important to job satisfaction than the congruence between perceived and preferred styles (Savery, 1993).

The practical upshot of job satisfaction and positive employee attitudes is that in addition to the benefits realized by employees, organizations benefit from higher perceptions of customer service. Schmit & Allscheid (1995) simultaneously studied samples of both employee attitudes and the company’s customers’ perceptions of quality service. The results indicated that there was a relationship between positive employee attitudes and perceptions of customer service.

Compensation

Although workers generally report that having an interesting and meaningful job is the main key to job satisfaction, good compensation and rewards systems and meaningful performance management processes can enhance employer-employee relationships. Accordingly, inequitable or ineffective systems can result in reduced levels of satisfaction.

Compensation and Rewards.

Compensation is affected by both external and internal factors (Sherman & Bohlander, 1992). External factors include labor market conditions, local wage rates, collective bargaining efforts and governmental regulation. Internal factors include the employer’s ability to pay, worth of the job, and the value of an employee’s relative contribution. Also important to compensation systems are fringe benefits. Fringe benefits often add 25 to 30 percent to compensation costs, over and above base salaries (Penson, 1995).

Compensation plans traditionally have been formal plans rooted in job hierarchy and individual performance, controlled by a bureaucratic human resources function. Recent trends indicate a shift, to more flexible models focusing on team and organizational performance, with control of compensation decisions fixed more with line managers and even workers (Risher, 1997). Risher (1997) notes that the structure of organizations is becoming more team oriented, resulting in the need to compensate individuals to some extent based upon their contributions to achieving team and organizational goals.

Compensation systems have not kept pace with organizational structures that utilize more work teams. In a recent survey, 87 percent of responding companies reported use of work teams, but only 41 percent offered some form of team-based compensation (“Paying for teamwork”, 1997). While few advocate dropping all considerations of individual employee performance in compensation decisions, the importance of team achievements should not be overlooked. It is also important to assure that emphasis on team performance is not undermined by the rewards system. For example, it would be difficult to focus employee efforts on team achievements if a piece-work incentive is in place (“Paying for teamwork”, 1997).

As reengineering efforts have revised work processes, organization structure has become flatter and more work teams are utilized (Flynn, 1996). Compensation and rewards systems need to be reviewed in light of these developments. Broadbanding is an attempt to increase flexibility in compensation plans in order to deal with compensation issues based upon team and productivity issues. Broadbanding is an infrastructure concept which allows compensation schemes to incorporate elements other than pay grades or ranges in determining pay and bonuses (Schuster & Zingheim, 1996). Essentially, broadbanding allows pay ranges to vary more so that compensation can include incentives other than those related strictly to individual performance. Advantages include reducing the hierarchical pay grade focus, providing more flexibility in determining employee rewards, and giving managers more power and latitude in compensation-related decisions (Flynn, 1996).

Contributions to productivity by individuals and teams are recognized through gainsharing (Jackson & Roper, 1996). Gainsharing provides compensation based on operational, financial or team performance (Masternak, 1997). Masternak (1997) studied 17 facilities involved in gainsharing plans. He suggests several elements that contribute to an effective gainsharing plan:

1. Each organization should customize gainsharing plans according to the nature of individual plants, locations, or business units.

2. Structured employee participation is necessary, particularly in developing fair and achievable performance baselines and goals.

3. Regular communication of performance goals and gainsharing results.

4. Provide individual, team and organizational recognition to promote the gainsharing plan and maintain employee focus.

5. Support the gainsharing plan by providing employees the resources for success, including training.

6. Payments related to productivity should become significant over time, and distributed frequently in order to sustain momentum.

7. Maintain organization-wide commitment to the plan.

Changes in the nature of relationships between suppliers and customers have provided the basis for other trends in compensation, especially in sales. Many customers have shifted their purchasing strategy from one of low initial cost to one that considers the total value (including quality and service issues in addition to costs) of the product to the customer (O’Connell & Marchese, 1995).

This trend has resulted in many firms reducing their number of supplier relationships drastically, which has resulted in pressures to reward salespersons appropriately for retaining customers, not just acquiring new business. This has led firms to develop life cycle compensation systems to help retain sales representatives (and their established client bases) throughout their entire careers. These new plans include awarding bonuses for accounts retained and contracts renewed, and recurring payments in consideration of multi-year sales results.

Another recent trend involves increased flexibility in employee benefit choices and administration. Owens-Corning, for example, has reduced the fixed level of guaranteed benefits in favor of employee credits. These credits can be used to purchase traditional fringe benefits, as well as other rewards such as time off or even additional money (McCafferty, 1996).

Performance Management

In order for employees to be accountable and rewarded for performance it is necessary to develop individual and team performance objectives, determine reward structures, and provide clear feedback of performance results (Jones, 1996). According to Sherman and Bohlander (1992), a performance management system has four objectives:

1.To allow employees to discuss performance issues and standards with supervisors on a regular basis.

2.To allow supervisors to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of employee performance.

3.To provide a mechanism for developing individual performance improvement programs.

4.To provide a basis for compensation decisions.

Additionally, regular performance appraisal serves as a means of documenting performance which can serve as a basis for disciplinary decisions, thereby providing notice to employees as part of due process. One positive result of good performance measurement is that it can provide insight into training needs to support an organizational development plan.

The predominant trends in compensation, rewards and performance management relate to individual and team incentives. Many organizations have flatter structures due to reduction in organizational layers and other elements of bureaucracy (Flynn, 1996). Compensation based upon individual, team, and organizational performance is gaining acceptance. Managers have assumed more responsibility for compensation administration and pay decisions (Flynn, 1996). Elements of employee responsibility for the success or failure of their employers is becoming a focus of compensation, rewards and performance management.

Empowerment

Recent trends toward flatter organizational structures and use of work teams have resulted in increased pressures on employees in terms of both performance and decision making. In order to succeed in this environment, employees must have the knowledge and resources, and organizations must empower employees through training, development and concern for their wellness.

Training

Training is a particularly important component of the development and learning process. Nadler and Nadler (1994) have developed the Critical Events Model (CEM), an open systems model designed for the systematic implementation of training and learning programs. Implementation of the CEM is a sequential process which includes the following components:

1.Identifying the needs of the organization. This involves discussions with managers and other diagnostic efforts to determine the goals and objectives of the training. The diagnosis is followed by evaluation and feedback.

2.Specify job performance. Discussions with first line supervisors and employees helps determine job performance in terms of quality and quantity.

3.Identify learner needs. This involves analysis of the gap in knowledge, skills or abilities to be addresses by the training in order to achieve the desired level of performance.

4.Determine objectives. The specific measurable objectives are derived from analysis up to this point in the process.

5.Build curriculum and select instructional strategies. This involves determining the content of the training and the methods of delivery. Choices for delivery techniques include general to specific, specific to general, and concrete to abstract concept techniques.

6.Obtain instructional resources. This includes development of reference materials, physical space and scheduling considerations.

7.Conduct the training. An opening meeting is conducted, reference materials are distributed, and the training schedule is begun.

8.Evaluation and feedback. Both during training, to correct for any weaknesses determined in the process, and at the conclusion of training, to determine its effectiveness.

Organizational Development.

In addition to training efforts, which generally provide process-related instruction, organizational development interventions are used to improve the social functioning of organizations, using behavioral science techniques applied to organizational processes. They focus on interactions among people within organization, with the goal of increasing organizational effectiveness and health (Hodge, et al., 1996).

Organizational development can target both the structural and process dimensions of an organization (Theodore, 1996). The support for planned organizational change must come from top management, but in order to be effective, change has to affect all employees involved. The components of organizational development may include gathering information from workers and providing feedback, study of organizational processes, team building, and various types of training (Hodge, et al., 1996).

Neuman, Edwards and Raju (1989) conducted a meta-analysis of organizational development interventions to determine their effects on satisfaction and attitudes. This analysis divided organizational development interventions into three categories: human processes, techno-structural, and multi-faceted interventions.

Human processes organizational development interventions include laboratory training, participation in decision making, goal setting, team building, grid OD, survey feedback techniques, and management by objectives. Techno-structural interventions include job redesign, job enlargement, job enrichment, and flextime. Multi-faceted interventions use combinations of intervention techniques.

Multi-faceted interventions proved to have greater impact in modifying satisfaction and attitudes than any single technique. Of the individual interventions, team building and lab training had the greatest impact on changing attitudes and satisfaction. Overall, the authors concluded that organizational development appears to affect attitudes more than satisfaction (Neuman, et al., 1989).

Management development is another key element of the empowerment and development process. The development of management competencies required for implementing strategic change and enhancing the understanding of competition is the focus of Holistic management (Wilson, 1994). According to Wilson (1994), this is accomplished by emphasizing “functional relationships between the organization’s parts and the whole” (p. 12).

Holistic management involves both quality systems and human resources; both the way individuals work and the way they are trained (Hoare, 1995). Successful implementation of strategies through the holistic approach requires a shared vision communicated throughout the organization, communicated through a strategic plan which has been endorsed by top management (Wilson, 1994).

Employee Health and Wellness

The American Institute of Stress estimates that illnesses related to stress cost the American economy $150 billion per year in terms of lost productivity and health costs (Minter, 1991). A recent survey by Harris Research found that of 5,400 adults in 16 countries, 54 percent reported that the leading cause of stress was work (Romano, 1995). Job and career path uncertainty is the top cause of workplace stress, but other factors such as poor communications and perceptions of workload inequity contribute as well (Minter, 1991).

Holmes and Rahe (1967) defined “stress” or “stressor” as any environmental, social, or internal demand which requires the individual to readjust his or her usual behavior patterns. Stressors related to organizations include factors intrinsic to the job, organizational structure and control, reward systems, and leader relationships (Ivancevich & Matteson, 1987).

Research over the past few decades has linked personality to stress-related illnesses, especially coronary heart disease. The “Type A” behaviors associated with susceptibility to stress-related illnesses include hard-driving, competitive, aggressive, hostile, and time-urgent behaviors (Ivancevich & Matteson, 1987).

Addressing the problems of workplace stress, including those exacerbated by Type A personality factors requires a concerted effort. Dewe (1994) suggests that many stress interventions fail because they offer only a partial solution or place the burden for change on the individual. Dewe (1994) suggests a three-level approach to the problem:

1. Primary interventions - reduce organizational-level stressors such as poor communications, role ambiguity, poor leader relationships, and red tape.

2. Secondary interventions - equip individuals to better cope with stress through relaxation training, meditation, biofeedback, cognitive restructuring, and exercise.

3. Tertiary interventions - assist individuals who have stress-related illnesses through Employee Assistance Programs and wellness programs.

Maintaining the health and well-being of employees is critical to productivity and employee satisfaction. Given the costs associated with this problem, both in terms of financial and human capital, employers must be pro-active in dealing with these issues.

Selection

Managing human capital involves a great deal of emphasis on selecting the right employees for the organization and for specific jobs. Effective employee selection is important, as the cost of replacing an employee is estimated by the U.S. Department of Labor to cost an employer one-third of an employee’s salary to acquire a replacement (White, 1995). Employee selection methods include employment interviews, assessment centers, realistic job previews, and the use of a variety of test instruments.

Employment interviews are the most widely used method of assessment, but their reliability is suspect, as they rarely show correlations with performance greater than .20 (Lane, 1992). However, Pulakos and Schmidt (1995) found that experience-based interviews derived from thorough job analysis found correlations with supervisory ratings as high as .32, indicating that this type interview can be a good predictor of performance.

Assessment centers utilize a variety of methods to judge performance, including in-basket exercises, leaderless group sessions, often complemented by cognitive ability and personality tests. According to Dulewicz (1991), assessment centers are the best predictors of future performance of all generally researched assessment tools, and can provide correlations with performance as high as .43 (Lane, 1992). Although considered rather costly, assessment centers have the advantage of showing little adverse impact on any protected group (Lane, 1992). Determining key competencies through job analysis and thorough training of assessors improves the validity of assessment center ratings (Dulewicz, 1991).

Realistic job previews are used by organizations to provide potential employees a balanced picture of the positive and negative aspects of the jobs they are seeking. The use of realistic job previews has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on job satisfaction and to be negatively correlated with turnover (Collari & Stumpf, 1995).

One author estimates that 5,000 to 6,000 employers use personality tests as part of their hiring processes (O’Meara, 1994). Research suggests that personality tests can be better predictors of job performance if the factors that comprise effective performance in a specific job are clearly understood, and even then, should be used to complement other methods and not as a stand-alone selection tool (Adler, 1994).

Barrick and Mount (1991) classified results from 117 criterion-related personality studies into personality dimensions according to Norman’s “big five” taxonomy. The “big five” personality dimensions are Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience.

Analysis across occupational categories revealed that Extraversion was positively correlated with performance in management and sales jobs, ones which involve good interpersonal skills. Agreeableness was expected to be positively correlated with performance in management and sales, but very little support was found for this hypothesis.

The Emotional Stability dimension was expected to predict success across all occupational groups, but actual correlations were, in fact, mixed (even negative for management jobs). The most consistent predictor of performance across occupational types was the Conscientiousness dimension. The authors found that the Openness to Experience and Extraversion dimensions were associated with training proficiency.

In order to use personality factors in the selection process to predict performance, it is necessary to choose an instrument. Employers must be concerned whether an ostensibly neutral employment practice such as personality testing can be shown to have an adverse impact on a protected group or invade privacy, (O’Meara, 1994).

Conclusions

The FACES model provides a framework for enhancing the effectiveness of people in organizations. Employee-organization fit, employee attitudes, effective compensation and performance management systems, employee empowerment, and effective selection methods are components of the internal organizational environment which, if optimized, contribute to achieving this goal.

References

Adler, S. (1994). Personality tests for sales force selection: Worth a fresh look. Review of Business, 16, 27 - 31.

Barney, J. B. (1995). Looking inside for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Executive, 9, 49 - 61.

Barrett, R. S. (1995). Employee selection with the performance priority survey. Personnel Psychology, 48, 653 - 662.

Barrick, M. R. & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 78, 111 - 118.

Bretz, R. D. & Judge, T. A. (1994). Person-organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 32 - 54.

Chase, N. (1996). The new face of reengineering: Process design grows up. Quality, 35, 43 - 48.

Collarri, S. M. & Stumpf, S. A. (1995). Compatibility and conflict among outcomes of organizational entry strategies: Mechanistic and social systems perspectives. Behavioral Science, 35, 1 - 10.

Dewe, P. (1994). EAP’s and stress management: From theory to practice to comprehensiveness. Management Review, 23, 21 - 32.

Dulewicz, V. (1991). Improving assessment centres. Personnel Management, 18, 4 - 6.

Flynn, G. (1996). Compare traditional pay with broadbanding. Personnel Journal, 75, 20, 26.

Hoare, C. (1995). A holistic management system. TQM Magazine, 7, 57 - 61.

Hodge, B. J., Anthony, W. P., & Gales, L. M. (1996). Organizational Theory: A Strategic Approach, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentiss-Hall.

Holmes, T. H. & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social adjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213 - 218.

How satisfied are your employees? (1997, Sept.) HR Focus, 12.

Ivancevich, J. M. & Matteson, M. T. (1987). Controlling work stress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jackson, III, J. & Roper, K. (1996). In any field, gainsharing can boost business. Triangle Business Journal, 12, 14Q.

Jones, D. D. (1996). Repositioning human resources: A case study. Human Resource Planning, 19, 51 - 53.

Lane, J. (1992). Methods of assessment. Health Manpower Management, 18, 4 - 6.

Masternak, R. (1997). How to make gainsharing successful: The collective experience of 17 facilities. Compensation and Benefits Review, 29, 43 - 53.

McCafferty, J. (1996). Rewards and resources in the pink. CFO, 12, 11.

Minter, S. G. (1991). Relieving workplace stress. Occupational Hazards, 53, 38 - 42.

Morris, T. (1995). Employee satisfaction: Managing the return on human capital. CMA Magazine, 69, 15 - 17.

Nadler, L. & Nadler, Z. (1994). Designing Training Programs, 2nd ed., Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

O’Connell, B. & Marchese, L. (1995). Paying for the relationship, not just the sale. Journal of Compensation and Benefits, 11, 32 - 39.

O’Meara, D. P. (1994). Personality tests raise issues of legality and effectiveness. HR Magazine, 39, 97 - 100.

Neuman, G. A., Edwards, J. E., & Raju, N. S. (1989). Organizational development interventions: A meta-analysis of their effects on satisfaction and other attitudes. Personnel Psychology, 42, 461 - 483.

Paying for teamwork: Winning compensation strategies. (1997). Getting Results…From the Hands-On Manager, 42, 6 - 8.

Pulakos, E. D. & Schmidt, N. (1995). Experience-based and situational interview questions: Studies of validity. Personnel Psychology, 48, 289 - 308.

Risher, H. (1997). The end of jobs: Planning and managing rewards in the new work paradigm. Compensation and Benefits Review, 29, 13 - 19.

Romano, C. (1995). Too much work causes stress. Management Review, 84, 6.

Rynes, S. L. & Gerhart, B. (1990). Interviewer assessments of applicant fit: An exploratory investigation. Personnel Psychology, 43, 13 - 35.

Savery, L. K. 91993). Difference between perceived and desired leadership styles: The effect on employee attitudes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 8, 28 - 32.

Schmidt, M. J. & Allscheid, S. P. (1995). Employee attitudes and customer satisfaction: making theoretical and empirical connections. Personnel Psychology: 48, 521 - 536.

Schuster, J. R. & Zingheim, P. K. (1996). The network discusses: Broadbanding, merit pay, and team participation. Compensation and Benefits Review, 28, 21 - 22.

Sherman, A. W. & Bohlander, G. W. (1992). Managing Human Resources, 9th ed., (pp. 303 - 338).

Sims, R. L. & Kroeck, K. G. (1994). The influence of ethical fit on employee satisfaction, commitment and turnover. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 939 - 947.

Theodore, J. D. (1996). Organizational Development. Unpublished paper. JDT Management Consultants, Lakeland, FL.

White, G. L. (1995). Employee turnover: The hidden drain on profits. HR Focus, 72,

15 - 18.

Wilson, J. G. (1994). Holistic management systems. Management Services, 38, 12 - 14.